Scientists have not ruled out sending Dawn on a journey across the solar system to another destination, a voyage that counterintuitively might burn less of the craft’s remaining hydrazine propellant than if Dawn stayed in orbit around Ceres, where it has resided since March 2015.

Dawn’s primary mission ended in June 2016, and NASA officials approved a one-year extension that expires June 30. The fate of Dawn after June 30 remains uncertain, but senior managers at NASA Headquarters are expected to soon decide whether the spacecraft should be turned, continue exploring Ceres, or depart the dwarf planet and perhaps fly by an asteroid.

“We are in the process of assessing with NASA options for a second extended mission,” said Carol Raymond, Dawn’s deputy principal investigator at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Raymond said Tuesday at a meeting of NASA’s Small Bodies Assessment Group, a community of asteroid and comet scientists, said one option for Dawn’s future could be to send the probe away from Ceres to encounter an asteroid.

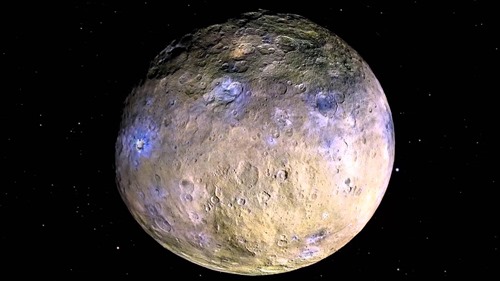

Otherwise, Dawn could remain at Ceres for further exploration of the previously-unvisited world, a dwarf planet with a diameter matching Texas’s, and the largest object in the asteroid belt.

The Gray landscape of Ceres is scattered with impact craters, some of which contain salt deposits in the form of bright spots that greeted scientists with mystery as Dawn arrived in early 2015.

Dawn also found evidence of an ice-rich later in Ceres’s crust just below the world’s charcoal-coloured surface, and scientists believe Ceres harboured an underground ocean in the past.

The mission also discovered a tenuous, temporary atmosphere around Ceres, and scientists have linked its fluctuations to the intensity of the solar wind.

The solar-powered spacecraft, fitted with solar array wings spanning 65 feet (19.7 meters) tip-to-tip, was built by Orbital ATK and launched from Cape Canaveral aboard a United Launch Alliance Delta 2 rocket in September 2007.

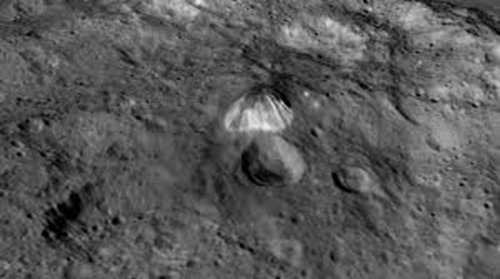

The mission has exceeded all of its scientific objectives, and the last year of bonus operations at Ceres included extra imaging of the dwarf planet, and a unique “opposition” observation in late April that positioned the Dawn spacecraft directly between the sun and Occator Crater.

Scientists hoped the favourable sun angle would yield new insights about the bright salt material inside Occator.

Dawn lost the third of its four reaction wheels — spinning devices similar to gyroscopes which use momentum to control the craft’s pointing — April 23, less than a week before the opposition observation opportunity.

The science campaign went ahead as planned after ground controllers restored Dawn to its regular flight mode, but using hydrazine-fuelled rocket thrusters instead of reaction wheels.

Dawn’s first reaction wheel failed in 2010, before it reached Vesta. A second wheel stopped working in 2012 as the craft’s ion propulsion system drove Dawn away from Vesta for the trip to Ceres.

Engineers designed Dawn to control its attitude, or orientation, in space with three reaction wheels, one for each pointing axis. A spare fourth reaction wheel was added for redundancy.

Experts from JPL and Orbital ATK devised a hybrid method of controlling Dawn’s attitude with the two remaining reaction wheels and hydrazine thrusters, the spacecraft now must fully rely on its rocket jets, wrote Marc Rayman, Dawn’s chief engineer at JPL, in a mission update posted on a NASA website.

“With the third wheel failure, we can be grateful that each wheel provided as much benefit as it did,” Rayman wrote. “The wheels allowed Dawn to conduct extremely valuable work while using the hydrazine very sparingly.”

Raymond said Tuesday that the third reaction wheel failure was “certainly not a mission-ending event, but it does reduce our lifetime because we have to use the hydrazine at a faster rate.”

“The amount of hydrazine Dawn uses depends on its activities,” Rayman wrote last month. “Whenever it fires an ion engine, the engine controls two of the three axes, significantly reducing the consumption of hydrazine.

“In orbit around Vesta and Ceres, the probe often trains its sensors on the alien landscapes beneath it. The lower the orbital altitude, the faster the orbital velocity, so Dawn needs to turn faster to keep the ground in its sights,” Rayman wrote. “Also, the gravitational attraction of these massive worlds tends to tug on the unusually large solar arrays in a way that would turn the ship in an unwanted direction. That force is stronger at lower altitude, so Dawn needs to work harder to counter it.

“The consequence is that Dawn uses more hydrazine in orbit around Vesta and Ceres than when it is journeying between worlds, orbiting the sun and manoeuvring with its ion engine. And it uses more hydrazine in lower orbits than in higher ones,” Rayman wrote.

There is plenty of xenon gas left aboard Dawn, officials said.

Raymond said Dawn is currently in an egg-shaped orbit around Ceres that ranges in distance between 12,000 miles (20,000 kilometres) and 30,000 miles (50,000 kilometres). The probe travelled as close as 240 miles (385 kilometres) to Ceres last year.

“We have enough resources, hydrazine and xenon, to support operations through at least the end of 2018,” Raymond said. “That will be depending the decision at (NASA) Headquarters what we will do with those resources.”

That lifetime prediction depends on Dawn remaining far away from Ceres.

“Lifetime at a lower altitude would likely be limited to weeks at this point,” she said.

A decision on Dawn’s future in the coming weeks — whether it will stay at Ceres or head elsewhere — echoes a similar stay vs. go choice that faced NASA managers last June.

Dawn’s science team last year proposed dispatching Dawn toward asteroid Adeona, a primitive, carbon-rich remnant from a collision that destroyed a much larger body, for a relatively slow-speed flyby in May 2019, but NASA officials decided keeping the probe in orbit around Ceres would yield a greater scientific return.

One possible fate has been ruled out.

Scientists don’t want Dawn to collide with Ceres and potentially spoil future exploration of the airless world.

“When our planetary protection requirements were negotiated, (scientists) already made the prediction that Ceres was an ocean world in the past, and could possibly be an ocean world today,” Raymond said. “We’ve been vindicated, so our planetary protection requirement was don’t land, don’t crash.”

Before shutting off Dawn for good, navigators will ensure the spacecraft is on a “quarantine” trajectory that avoids impacting Ceres, she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment